Is Music a Universal Language?

The four universal musical genres, Outernational Dance EP out now on Multi Culti, Zamenhof's Esperanto language, Birdsong, Bone Flutes, Annie Mac.

We know that music has existed since the earliest homo sapiens roamed the planet, tens of thousands of years ago. The 60,000 year old Neanderthal bone flute and other primitive instruments are testament to that, as are pre-historic cave paintings depicting musical scenes. It is highly plausible that music back then was a communication device, an accompaniment to ritual, a means of uplifting a celebratory event, a way to drive motivation in the face of war or battles, and a means of soothing and sleep for infants and others - not dissimilar to how it is used now.

Music, if divided into its constituent parts - melody, harmony, rhythm etc, triggers specific neurological processes, that serve clear and defined functional roles within the brain. Strip away any cultural component and refine it back to Edgard Varèse’s definition of ‘organised sound’, one can observe music’s core feature in the relationships between frequency, working primarily on our emotional and motor systems (with memory and other brain systems coming later).

However, if you are to ask ChatGTP if music is universal, you get the following response:

Music can transcend many language barriers and convey emotion globally, but it’s not a truly universal language in the strictest sense. It’s more accurate to say that music has universal elements, but its full meaning is shaped by culture.

Is birdsong music?

A recent conversation between ex-Radio 1 DJs Annie Mac and Nick Grimshaw dived into this question. Annie, rightfully in my opinion, said “of course birdsong is music” - and that stands to prove my point above- birdsong music doesn’t have any cultural context and most likely predates (or at least co-evolved alongside) human music.

The trouble is, in the current day, the definition of what ‘music’ is has become a little muddled. The music industry, created on the back of the advent of recorded music (and sheet music publishing), has only been a relatively recent phenomenon when you compare its 120 year existence to music’s 60,000 year history. Commercialisation of music, through recordings and ticketed performance has created a gap between listener and musical performer, and also birthed many musical cultures in the form of movements, scenes, genres etc.

The four musical genres

A meta analysis of all music conducted by Harvard found that once the cultural component had been stripped away, there are only really four genres:

Love Songs

Lullabies (Sleep Songs)

Dance Songs

Healing Songs

They found some commonality in the way each culture has found ways to construct these sounds that are played with the instruments, scales and tuning systems that are traditional to that location.

Music appears in every society observed. Across societies, music is associated with behaviors such as infant care, healing, dance, and love (among many others, like mourning, warfare, processions, and ritual). Examining lullabies, healing songs, dance songs, and love songs in particular, they discovered that songs that share behavioral functions tend to have similar musical features.

“Lullabies and dance songs are ubiquitous, and they are also highly stereotyped,” Singh said. “For me, dance songs and lullabies tend to define the space of what music can be. They do very different things with features that are almost the opposite of each other.”

Whilst it is hard to claim anything to be ‘universal’, I like the way this analysis helps get us back to true fundamentals: music as a form of communication and connection, serving distinct functional purposes and bonding us outside the confines of language, religion and cultural constructs.

Esperanto

Which brings me to Esperanto - the so-called ‘universal language’ concocted by Ludovic L Zamenhof in 1887. It was intended for use as a ‘universal second language - an auxiliary tongue by means of which all people, no matter what their origins, might communicate freely - it is a constructed thing, a deliberate invention that must be deliberately learned. In a period of time when the world was in flux, a global world order was slowly forming’(The Guardian). However, like this world order, Esperanto can be criticised for being overly European-centric:

For an English speaker, Esperanto is reckoned to be five times as easy to learn as Spanish or French, 10 times as easy as Russian and 20 times as easy as Arabic or Chinese.

While critics seize on the obvious downside of this Eurocentricity - namely that it puts speakers of other languages at a disadvantage - Esperantists argue that the regularity and simplicity of Zamenhof's scheme quickly outweigh any lack of familiarity with root words, and point to the popularity of Esperanto in Hungary, Estonia, Finland, Japan, China and Vietnam as proof of Zamenhof's pudding. Apart from its logical construction, Esperanto has another appealing characteristic: it is phonetic and orthographic, meaning that each letter represents only one sound, and each sound is represented by only one letter.

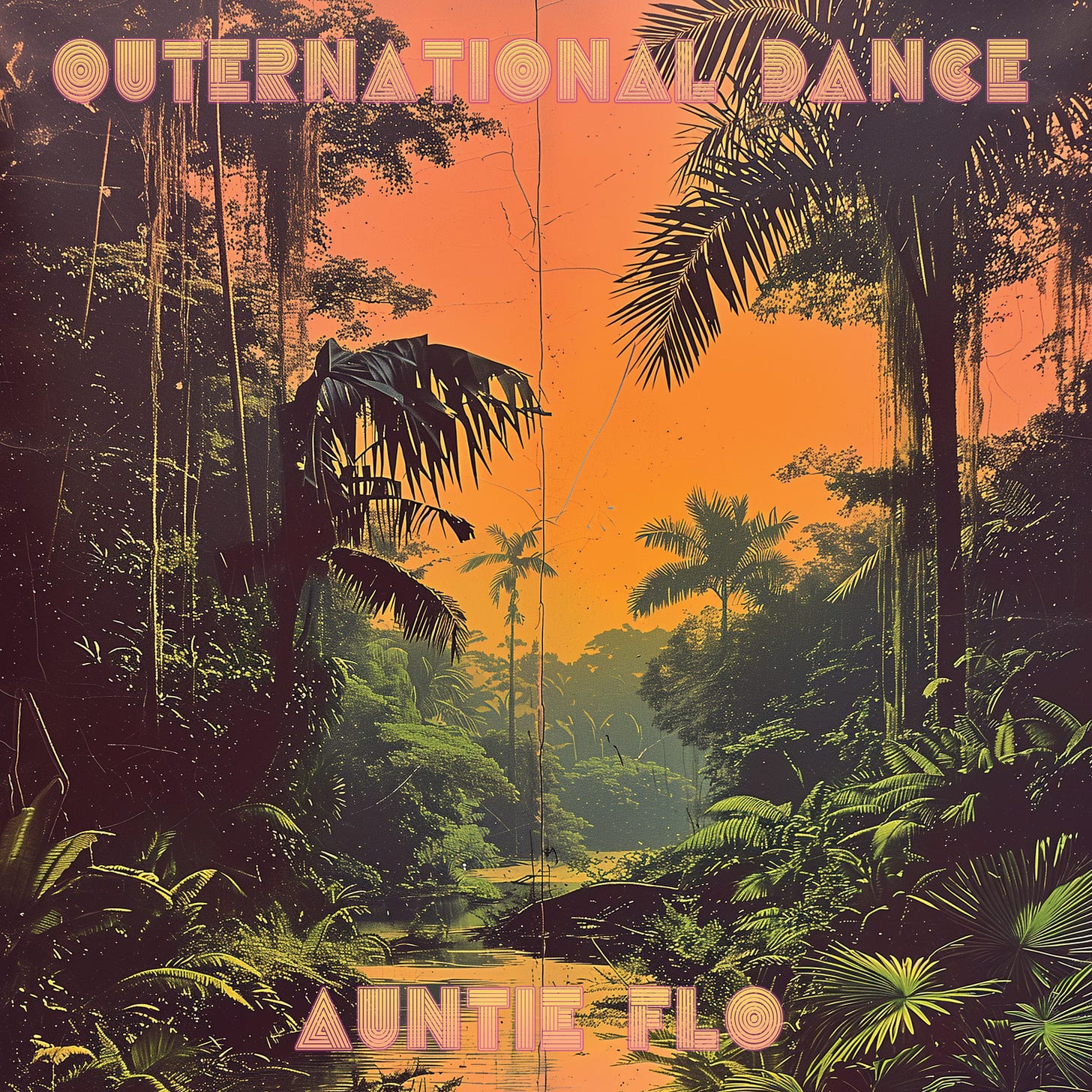

Whatever you think of it, Esperanto provided me with the inspiration behind my latest release: The Outernational Dance EP on the Multi Culti label. All the track titles were derived from the Esperanto language.

In the promotion of this release, we received some critique on the above definition, which hopefully this piece goes some way to answer. I understand the criticism but I’d urge we look past cultural norms and traditions to find the answers, however difficult that is.

What do you think? Is music a universal language?