In the age of AI, could some music become extinct?

Saving Goan Konkani Music with Lexan Freitas, a true musical digger. Human Curation versus AI. The rise of AI music in the age of over abundance

I spoke on a panel last night entitled ‘Human Curation versus AI’ alongside BBC6 radio host Jamz Supernova and Josh Mason from the hugely popular instagram blog account Somewhere Soul, hosted by Tim Garcia and Tina Edwards for KEF Loudspeakers.

It’s a topic that’s been close to my heart for a while. For 17/18 years, I ran a music curation company, Open Ear Music, and we made it our mission to push human curation as the best way to serve our clients, which included bars, restaurant, shops, gyms and workspaces. The definition of curation evolved over time, when we started in 2006/2007, the battle was to prove that curation of music outside of the mainstream pop charts could provide value for the businesses we worked with and their customers, whereas latterly it became more of a numbers game.

We were massive believers in the brilliance of independent music, and wanted to use the places we worked with as spaces of music discovery, at the same time helping the businesses carve out a unique sonic identity rather than playing the same stuff that their neighbours and competitors did.

We pushed to make this more of a foreground experience - calling it ‘playlists with personality’ and banning calling it ‘background music’. Our slogan was ‘unlike your eyes, your ears are always open’ - as the music we hear will always illicit some sort of emotional, behavioural or physiological response. The ears don’t blink after all.

Curation, done by humans was key and our small team had hungry ears - at our peak I was probably listening to over 200-300 songs every day, keeping on top of all the best new releases from a range of our independent label partners - our library topped 250,000 songs and was all killer, no filler.

As time progressed, being a curator evolved: streaming dramatically and exponentially increasing supply to an overwhelming amount - currently 100,000 song are uploaded daily - that’s 36.5million new songs per year. The ease of access to the world’s music via streaming also turned the average listener into curators too, more likely to personalise their own playlists - genres and eras became fractured and it became normalised for one to like ‘everything’ although technically that was impossible.

Overadundance of music created the need for better filters and AI became a necessary tool. No human could keep on top of the sheer volume of music that is now being released.

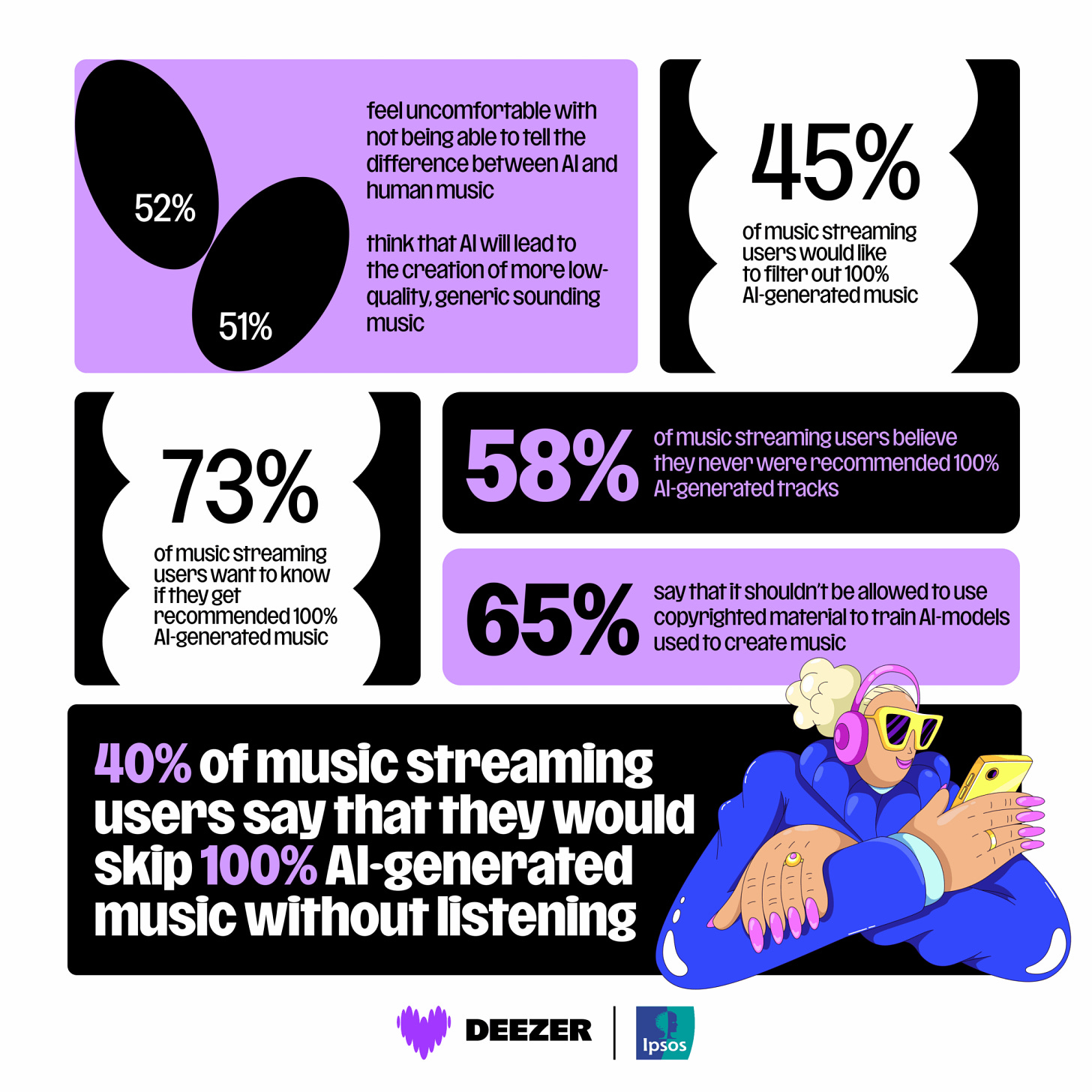

Now, with AI generated music here and rapidly expanding, curation is faced with its next evolution - is it important to create a distinction between AI music and Human music? Maybe we’re already too late, with AI music currently topping the country charts in the US and only 3% of people recently surveyed in Deezer able to tell the difference.

I joked with my friends that I make human music for the 3%.

The panel concluded with a call to arms: let’s not lose sight of the precociousness of music created by humans: the emotional, social and cultural connections that it brings. Let’s think about splitting the definitions of music between songs that are purely functional - music which serves us as a utility gushing through internet browsers versus music that contains more meaning, as an cultural artefact, as a pioneering step forward, and as art itself.

Music in Danger of becoming Extinct

With the sheer scale of this musical oversupply in mind, it’s easy to forget the scarcity that we were very recently faced with. The need not to ‘sleep’ on a release otherwise it would sell out, or where releases that only exist on physical media formats.

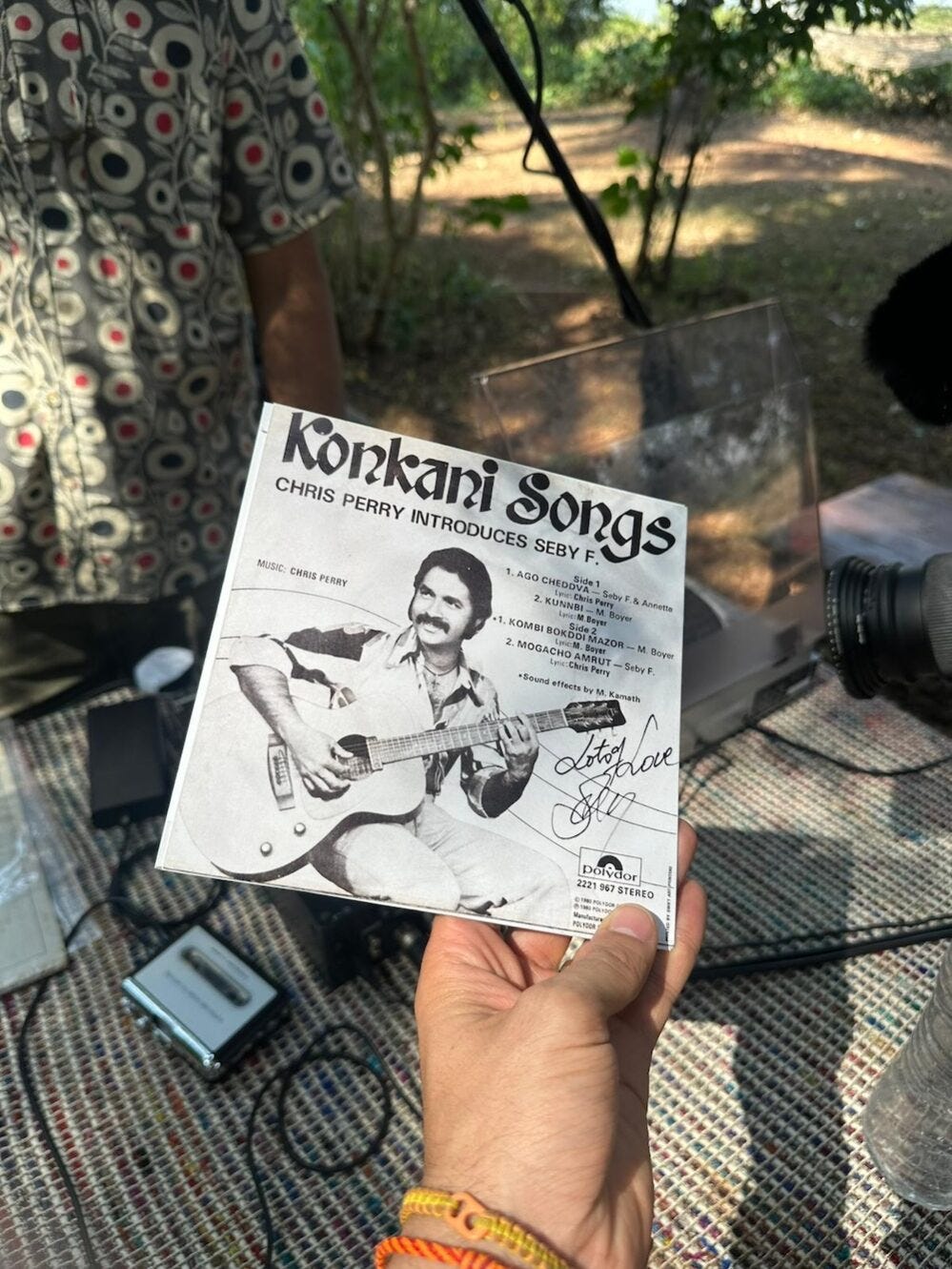

Earlier this year, I spent a week in Goa to perform at the incredible Sultry Mist Festival. I’ve been to Goa a few times before but never managed to buy any records there. So ahead of this year’s trip I was put in touch with one of Goa’s top musical diggers, Leaxan Freitas, who was kind enough to share his approach to finding rare Goan music

It’s an absolutely fascinating story of music pre-internet, where you sometimes have to wait for record owners to pass away before anyone can hear a song. Read it on Ransome Note

In an age where music streams instantly at our fingertips, Goan music tells a different story. Much of it exists only on degraded cassettes, dusty records, and brittle shellac discs, jealously guarded by collectors who treat them as sacred artifacts rather than commodities. Through his project, jokingly titled “Moldy Tapes from Goa” Freitas has made it his mission to preserve this disappearing repertoire, navigating protective owners, Goa’s unforgiving climate, and the natural decay of poorly manufactured formats.

Here is my interview with Leaxan recorded at the Loja in Goa, near the festival:

Brian: Hi Leaxan, how are you doing?

Leaxan Freitas: Doing good! It’s a lovely spot here, and I’m looking forward to doing more of what we’ve been sharing at the festival. All my work is on vinyl or tapes, which is quite a challenge to keep up. Goa has recorded music going back to 1928. 1908 was the first recorded song, but 1928 was the first I have been able to track down, starting with recordings on shellac discs and moving on to vinyl and later tapes. These records are really hard to find. For example, All India Radio, or Akashvani, has its own collection. Then there are private collectors like me and a few others. Most of the people I know who collect are around 20 years older than me, and they’ve been doing it since the records were originally available in stores. I started collecting in 2011, just after finishing college. By that time, it was already difficult to find them. And the quality varies; sometimes a disc has a song you want, but it’s full of crackles and skips. Sometimes you get lucky. I’ve got one disc that’s cracked, so two songs are gone, but the rest still plays fine. Or an EP where one side’s scratched but the other is perfect.

Nobody really sells Konkani records. It’s like an unspoken rule. If you have two copies, you can trade, but that’s about it. I’ve done trades here and there over the years—once I even traded three EPs for one LP. It’s not about quantity; it’s about the music and what it means. Having all this music on vinyl is special. When I was studying and living outside Goa, it kept me connected to home. I’d listen to these records, have some urak (Goan’s alcoholic drink made from cashews), and it would transport me back.

Brian: That was going to be my next question—why did you get into it in the first place?

Leaxan Freitas: It was definitely about staying connected to home. When you leave Goa for a city like Bangalore, you can’t get the same people, the beaches, the greenery, the food. Even at Goan restaurants, it’s never quite the same. The only thing you can really take with you is the music. And the music helps you stay in touch with the language too. When you’re not surrounded by people speaking Konkani, the songs keep you connected to the land and the culture. I started with digital versions, then cassettes, and eventually moved on to vinyl, building my collection bit by bit.

Brian: So some of this music is available digitally on Spotify and YouTube, but some isn’t, right?

Leaxan Freitas: Yeah, exactly. A lot of the music released by HMV, now known as Saregama, is online. You’ll find it on Spotify, YouTube Music, and other streaming services. But there’s a huge amount that isn’t available anywhere digitally. Some records I’ve only seen pictures of; I’ve never even heard the music.

Brian: It’s fascinating. You were saying before that these records are like antiques, pieces of art. Collectors don’t sell them; they just hold on to them for life, maybe trading occasionally.

Leaxan Freitas: Yes, absolutely. These collections often sit in homes like prized antiques. When someone passes away, they might just get given away. That’s why I feel it’s important to play this music publicly, at events or on radio, so it doesn’t just sit locked away. It should be heard.

Brian: You played a 100% Goan vinyl set on Friday at Sultry Mist. How did that go?

Leaxan Freitas: It was amazing. This was my third time doing a full Konkani vinyl set. I’d done it before at the Echoes of Earth festival in Goa. The response was fantastic. As far as I know, nobody else has performed an all-Konkani vinyl set live, so it felt special. There’s so much energy in the crowd when they hear something familiar yet rare. It’s been wonderful to see people reconnect with this music.

Brian: As someone of Goan heritage living abroad, I find it fascinating. Trying to understand the culture through music has been difficult from afar. There are a few compilations like the Smithsonian’s Mando recordings and some things on streaming services, but hearing these songs on vinyl, in their original format, is something very special.

Leaxan Freitas: Some of these records go back to the 1970s, and I even have a few older shellac discs. Goa’s weather isn’t kind to analog formats. Mold gets into the grooves, and the paper sleeves become brittle. As soon as I get a record, I clean it and transfer it into a new sleeve. I’ve scanned all the artwork to preserve it, because I can’t travel with the originals. Sometimes collectors reach out asking for scanned covers, and I’m always happy to share. If you have the record, you want the artwork to go with it.

Brian: And there’s also this amazing story about the bootleg cassettes, right?

Leaxan Freitas: Yes. While digging through old tapes, I noticed something strange: the bootleg cassettes often sounded better than the originals. The official ones were made in Bombay using lower-quality materials, while the copies made in the Middle East used TDK or Sony tapes. Many Goans were working in Dubai, Kuwait, or Muscat, and when they came home, one of the first things they brought back was a tape player. They’d record from All India Radio or make copies of their favorite songs. Ironically, those homemade or bootleg versions have lasted longer and often sound better today.

Brian: It’s funny, isn’t it? Back in the 90s people said, “Home taping is killing music,” but in this case, home taping actually preserved it.

Leaxan Freitas: Exactly. Without those tapes, a lot of this music would have disappeared. Sadly, the Goa branch of All India Radio shut down most of its Konkani programming last year. They used to air a few hours of music a day, and people would record songs off the radio. Those tapes are now part of history.

Brian: There’s a sense that Goan culture and language are under threat, especially with so many outsiders settling in. This kind of archiving feels more important than ever.

Leaxan Freitas: Yes, especially with Konkani. Unlike other Indian languages that have one main script, Konkani is written in both Devanagari and Roman scripts. Roman Konkani, which most Goan music is written in, doesn’t have the same official recognition as Devanagari. There’s now a push to give Roman Konkani equal status so that writers, musicians, and lyricists working in it can receive grants and recognition. If anyone questions its importance, they only need to look at the thousands of songs written and recorded in that script.

Brian: It sounds like a huge mission to preserve it all.

Leaxan Freitas: It is. Sometimes people hear about what I’m doing and donate tapes or records that were just lying around at home. That’s how I’ve been able to grow the collection. Records, though, are much harder to find.

Brian: Thanks for your time, Leaxan. We’re heading to the festival now, where you’ll be running a workshop on this topic and playing some of this incredible music.

Leaxan Freitas: Yes, and I’ve been thinking of calling the project Moldy Tapes from Goa (a tongue in cheek nod to ‘Awesome Tapes from Africa). I want to start putting material online, reviewing the tapes, describing the music, and sharing stories from the artists themselves.

Brian: That sounds amazing. For anyone who wants to explore more of this music, where can they find you online?

Leaxan Freitas: I’ve just started a website called cantaram.com.

Follow Leaxan

Art Deco inspired structures in Goa: Goenchideco

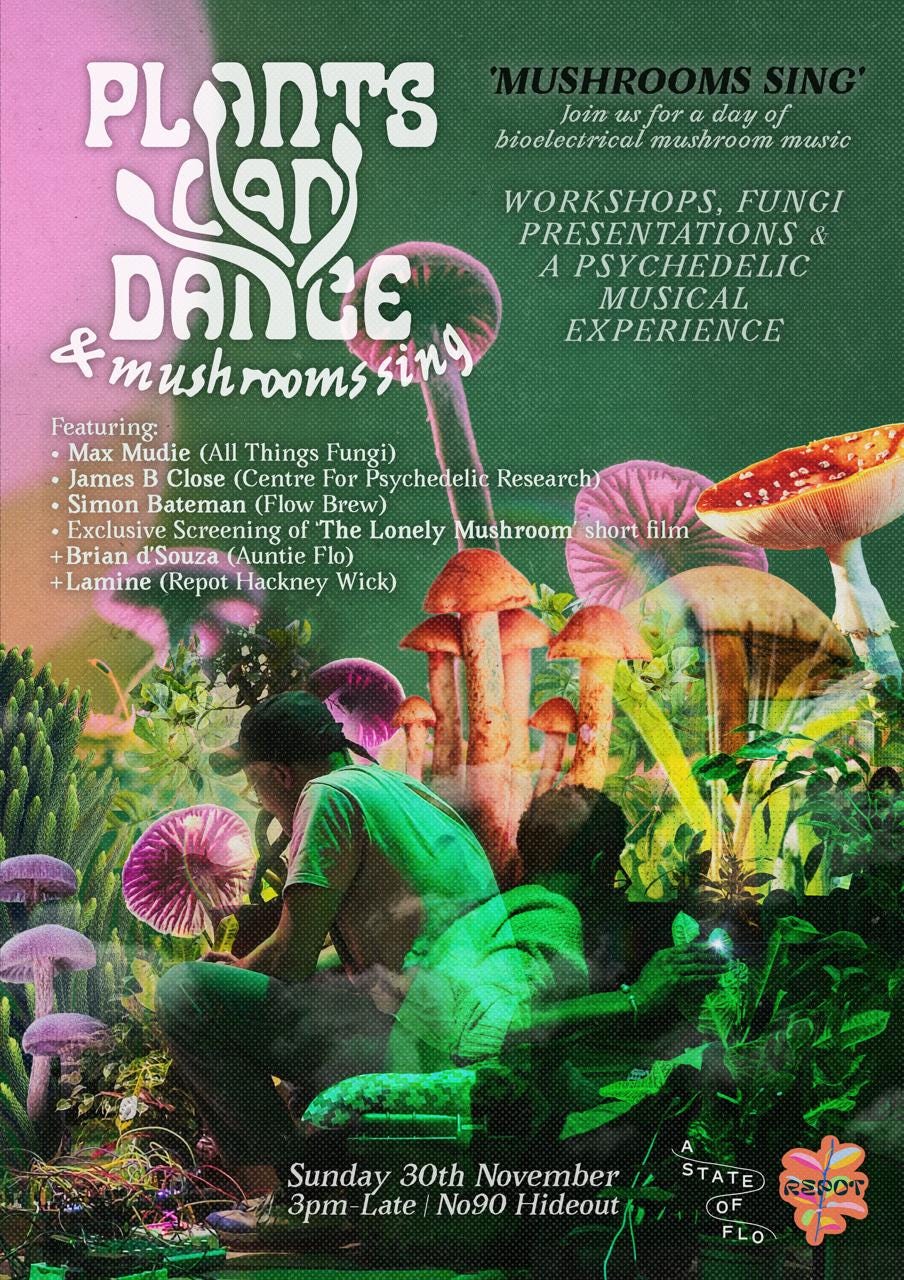

Anyone in London: Plants Can Dance (and Mushrooms Sing) is next Sunday 30th Nov.